Point of Interest One

Christ Church Tourmakeady

The Church of Ireland, Christ Church, Ballyovey, Tourmakeady

The Church of Ireland (COI) Church in Tourmakeady was built in the 1850’s and opened in September 1853. It was built by the COI Bishop of Tuam, Reverend Thomas Span Plunket (1792-1866), second Baron Plunket and 'Lord Bishop of Tuam Killala and Achonry Bishop of Tuam, who had taken up residence in Tourmakeady Lodge in 1831/2.

In 1852 Plunket increased his holdings to over 10,000 acres, and his 203 tenants were recorded as paying an annual rent of 2000 pounds. Plunket was a champion of the “second reformation”, an evangelical campaign which ran from the 1820’s to the 1860’s. These evangelical voluntary societies, such as the Irish Society and the Irish Church Mission focused their work on the poorer parts of Ireland, such as the Irish speaking regions of Munster and Connaught. This Protestant revival was promoted by Irish translations of the Bible, Irish speaking readers of scripture and the distribution of food. The most significant evangelical society, and possibly the most radical was the Irish Church Missions to Roman Catholics. The society was financed by subscriptions from England. The activities of this group were concentrated on the northern part of Connemara, in the Clifden area, Achill and the Lough Mask region in Mayo. Bishop Plunket and the first rector he appointed in Tourmakeady, Rev. Hamilton Townsend were strong supporters of the Irish Church Missions Society. Mission schools were established in Tourmakeady, Cappaghduff and Partry. Another school at Drimcoggy was opened and closed.

The work of the Irish Church Missions Society was initially focused on the work houses. In these desolate and poverty stricken institutions they were, according to themselves, very successful. The recovery of the country from the famine saw the populations of the work houses drop and the Missions Society turned its attention to educational matters. Schools in the more isolated regions of Ireland were poorly funded and the Missions Society saw the school going children, and the parents of these children, as a suitable population for the work of the Society. This was where Plunket and his schools ran foul of the local clergy. What became known as the “War in Partry”, was a conflict over the influence that the second reformation was having on the schools and more generally the education system. However an important part of the conflict focused on the tenancy of the parents of school going children who were expected to convert, and if they did not, were under threat of eviction.

(The fact that there was no war, though there was violence and tension, and that the events took place in Tourmakeady not Partry never stopped people referring to the dispute, mainly between Bishop Plunket on the one hand and the two Catholic Clerics Fathers Ward and Lavelle on the other, as the Partry Affair or more colourfully the “War in Partry”).

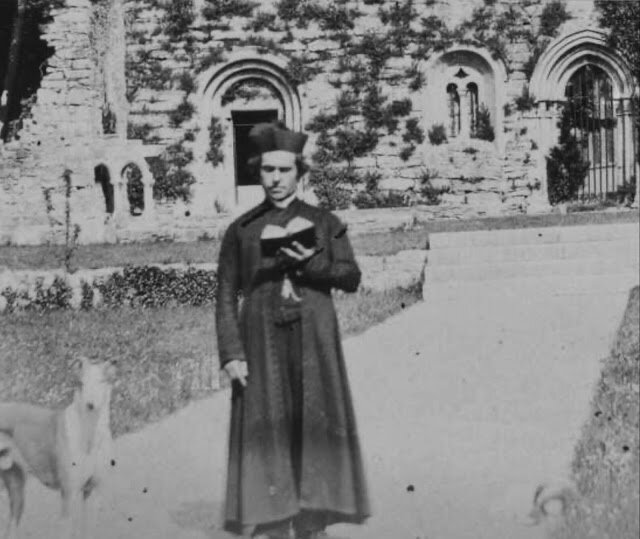

Christ Church Tourmakeady

The curate in Tourmakeady, Fr. Peter Ward, resisted Plunkets efforts and wrote to The Tablet newspaper saying his parish was “invaded with swarms of Jumpers, striving to seduce the poor at their dying hungry moments”, and that the Mission school in Cappaghduff was the scene, nightly, “of theatre where is enacted scenes of abuse and calumny against the Virgin Mother of God”. Ward went further in 1854 when he wrote that 104 people in 21 families were told that if they did not send their children to mission schools they would face eviction, and finally accusing Plunket of actively promoting proselytisation. (The term proselytisation came into common use in the 18th century and comes from the Latin proselyte, which means a new convert. In Ireland those who did convert from Catholic to Protestant were known as Jumpers or Soupers.) The Irish nationalist newspapers of the day gave a lot of space to Fr. Ward and his statement that Catholic tenants on Plunkets land had been evicted, were now homeless and destitute and that their places had been taken by Protestant tenants. More publicity came Fr. Wards way when he burned a bible to highlight the events. This led to his conviction in court, and to a lot of sympathy, in Ireland and beyond, as well as money subscribed to combat the actions of Bishop Plunket. Fr. Ward was replaced by Fr. Patrick Lavelle in 1858.

A former Professor of Philosophy in the Irish College in Paris, Lavelle would prove to be more than a match for Plunkett. A colourful and controversial character, he left his post in Paris under threat of arrest and would later steal the Cross of Cong while in that Parish. This incident occurred in the Royal Irish Academy in Dublin, where the Cross was kept, and Lavelle, after asking to see the Cross of Cong put it under his cassock and walked out with it. He was arrested on his way to the train station. Lavelle was an avid letter writer and a more stalwart foe than Ward. Lavelle set to work preaching to his parishioners about the dangers of the Mission Schools and within weeks there were reports of people throwing themselves on their knees in Church asking forgiveness. As a result only a handful of Catholic children remained in Mission schools and these were employees of Plunket who faced eviction or loss of employment if they took their children out of school. Five Catholic national schools were opened in the Parish in early 1859, largely funded by John McHale the catholic bishop of Tuam.

However Lavelle was also pursuing his own tactics of confrontation with those he saw as the promoters of the second reformation, the mission teachers, the mission agents and indeed non compliant parishioners. In sermons he warned parents who allowed children to attend these schools that they were exposing them to evil and danger. There are reports of people going on their knees at the altar seeking forgiveness, as a result. These episodes, sometimes violent, always full of tension led to Lavelle being in and out of court. It also meant he was in and out of the papers, and that the struggle in Tourmakeady, a struggle for the souls and survival of the catholic population was national news and that Lavelle was leading a struggle against the Irish Church Missions which required full support from all Irish Catholics. The Protestant Mission countered this argument by saying that “since that gentleman’s arrival (Fr. Lavelle) in Tourmakeady, the newspapers have had to record, day after day, acts of violence on the part of the people, and violent language on the part of the of the priest”. The violence, including a threat to shoot Lavelle by Richard Goodison, a missionary at Aasleagh, near Leenane, led to the establishment of four new police stations in the area. Tensions, already running high between the opposing sides, were brought to a head in January 1860 with the murder of Alexander Harvison, a Protestant employee of Bishop Plunkett from County Monaghant.

Fr Patrick Lavelle

Plunket’s grave in Christ Church Tourmakeady

Having spent an evening visiting local friends, Mr. Harvison called into Hewitts Bar at around 10 pm on the night of 31 January 1860, where he had a brandy. He left to go home, which was close by and near to Tourmakeady lodge, when he was fatally shot sometime between 11 pm and midnight. He was shot in the chest with a shot-gun. The fact that he died with his gun drawn indicates that he sensed his attacker was dangerous, and the fact that he owned a gun and had it in his possession while abroad in Tourmakeady shows the danger felt by him. The reason for the shooting was never established, although Harvison had caught a fellow employee of Plunket’s poaching, and this resulted in threats against Harvison. More mysteriously, on the night of the murder six sheep had been impounded for trespassing on Plunkets land. The men in charge of the pound, on hearing the attack and the general commotion, left to go to the aid of Harvison and his wife who was at home at the time of the murder and who, in the company of a neighbour had found the body of her husband. When they returned to the pound the trespassing sheep had been liberated. The murder resulted in increased tensions between the two communities, more letters to the papers and more court appearances for Lavelle.

One of these court appearances had to do with the removal of an animal pound that Plunket had erected beside the Catholic Church. The presence of sheep in the pound meant that Lavelle’s sermons had to contend with bleating sheep. Frustrated by this Lavelle one day led his flock from Mass in the Church and tore down the pound, for which he was subsequently charged.

An agreement between the parties was reached in Spring 1860 which brought some respite to the level of lawlessness in the area. However it proved short lived as in November 1860 Plunkett moved to evict a number of tenants. These families were not behind in their rent but were evicted for burning the land, summoning Bishop to court, or for assaulting scripture readers. He did this with the help of the constabulary and British troops. However these evictions were to be his undoing, as sympathy across the country and indeed in England was focused on the fate of the tenants, especially at the time of year they were evicted. Public opinion turned against Plunket and this was further enraged by him proceeding with more evictions in April 1861. The “War in Partry” was discussed in the House of Commons, featured in articles in the British and Irish press and resulted in Plunket becoming an object of vilification. In 1863 he sold his estate and moved to the Bishops Palace in Tuam where he died in 1866.

The whole “War in Partry” incident had important repercussions in broader Irish history. Not alone did it see the defeat of a proselytising mission, it also showed that the Catholic Church could defeat the forces of a landlord. The type of ministry espoused by Lavelle, berating his flock into submission with fire and brimstone sermons, for him “his most powerful weapon was his pulpit” and confronting the perceived enemy, was also to have repercussions for Irish Catholicism. The use of the Press to challenge the Missions tactics and to expose their methods was also to prove a valuable experience.